| You Are An INTP |

The Thinker You are analytical and logical - and on a quest to learn everything you can. Smart and complex, you always love a new intellectual challenge. Your biggest pet peeve is people who slow you down with trivial chit chat. A quiet maverick, you tend to ignore rules and authority whenever you feel like it. In love, you are an easy person to fall for. But not an easy person to stay in love with. Although you are quite flexible, you often come off as aloof or argumentative. At work, you are both a logical and creative thinker. You are great at solving problems. You would make an excellent mathematician, programmer, or professor. How you see yourself: Creative, fair, and tough-minded When other people don't get you, they see you as: arrogant, cold, and robotic |

Sunday, July 22, 2007

Personality test?

One part of me hates personality tests. The other partakes in them and posts the conclusions on his blog.

Wednesday, July 18, 2007

notes on terrorists

In an article from the Chronicle Review, Carlin Romano discusses terrorists and moral judgment. He points out that many people, especially our political leaders, refrain from attaching morally loaded terms to terrorists. Terrorists are never called "bastards, lowlife, cowards, scum", etc.

In response to a call for a better way to detect and discourage terrorists, Romano asks: "Why does such a better way not include a call for sterner moral judgment, forcefully expressed?" Why, that is, don't we call these terrorists names.

Well, I may have an answer. Morally loaded terms are not only means to describe people. When we call someone a lowlife we are not merely representing that person with a word. We are also trying to affect their behaviour. We are implicitly saying: "A lowlife is a bad thing to be. You are a lowlife. So make a change." But, in the minds of most people, the actions of terrorists are of a certain kind - one unlike the actions of "normal" people. They are so abominable that, perhaps, they are the work of individuals incapable of improvement and reform. Terrorists, it seems, are beyond reproach, deaf to our moral judgment. So why waste words on them if it will not alter their behaviour in the least?

If this line of reasoning is held by people in general, it may explain the phenomenon Romano discusses.

In response to a call for a better way to detect and discourage terrorists, Romano asks: "Why does such a better way not include a call for sterner moral judgment, forcefully expressed?" Why, that is, don't we call these terrorists names.

Well, I may have an answer. Morally loaded terms are not only means to describe people. When we call someone a lowlife we are not merely representing that person with a word. We are also trying to affect their behaviour. We are implicitly saying: "A lowlife is a bad thing to be. You are a lowlife. So make a change." But, in the minds of most people, the actions of terrorists are of a certain kind - one unlike the actions of "normal" people. They are so abominable that, perhaps, they are the work of individuals incapable of improvement and reform. Terrorists, it seems, are beyond reproach, deaf to our moral judgment. So why waste words on them if it will not alter their behaviour in the least?

If this line of reasoning is held by people in general, it may explain the phenomenon Romano discusses.

Wednesday, July 11, 2007

Eritrean journalists

This isn't news to most Eritreans. We know the dismal record of suppression in our state. Free speech is a platitude. And freedom of the press is actively curbed.

What a sad situation.

What a sad situation.

Sunday, July 8, 2007

more notes

From an article in the Walrus: "Zamenhof felt that the anti-Semitism and ethnic strife he witnessed were exacerbated by communication problems. His scheme for a planned international language was, in its optimism and scientific rationalism, quintessentially nineteenth century, but Zamenhof was also working within a larger tradition, one in which language is a bridge to a utopian dream of perfect understanding, of absolute harmony among what is meant, what is said, and what is heard. In this sense, Esperanto isn’t meant to be merely a convenient way to order a cup of coffee in a distant land; it is a way of imagining the future."

I'm not sure that ethnic strife is inflamed by a lack of communication. Rarely do ethnic differences erupt into spewing conflicts because of ignorance, a misunderstanding of the other group's beliefs and hopes. The Nazis, for instance, spoke the same language as many of the German Jews. The Nazis, however, simply didn't care about them and were unmoved at the sight of their suffering.

Having the whole world speak the same language, using the same sounds to signify the same things, will not change a thing.

Of course, at the individual level, learning another person's language will make you more sympathetic to their worldview and perhaps lead to something resembling harmony.

I'm not sure that ethnic strife is inflamed by a lack of communication. Rarely do ethnic differences erupt into spewing conflicts because of ignorance, a misunderstanding of the other group's beliefs and hopes. The Nazis, for instance, spoke the same language as many of the German Jews. The Nazis, however, simply didn't care about them and were unmoved at the sight of their suffering.

Having the whole world speak the same language, using the same sounds to signify the same things, will not change a thing.

Of course, at the individual level, learning another person's language will make you more sympathetic to their worldview and perhaps lead to something resembling harmony.

Saturday, July 7, 2007

Live Earth

Many are criticizing Live Earth for producing a lot of carbon emissions. They call it hypocritical. My question is this: might we gladly accept the relatively minimal harm Al Gore, David Suzuki, and others, wreck on our environment? Their work in advocating for greenhouse gas reductions, and environmentally friendly products, will change the habits of quite a few people. And so, in the long-run, these high-profile figureheads will probably effect more good than bad.

Nevertheless, I am not suggesting we leave them unaccountable. Let's just give them a bit of a break.

Nevertheless, I am not suggesting we leave them unaccountable. Let's just give them a bit of a break.

Thursday, July 5, 2007

metablog

I told myself I would have very few, if any, meta-entries. No entries about blogs (although I have one featuring a New York Times diagram of a blog's life-span). No entries about my own entries. And, on a similar note, no entries about what I'm up to. My blog is supposed to be a mirror of nature! Apologies to our recently departed Richard Rorty.

But I do make exceptions now and then. And here's one them:

But I do make exceptions now and then. And here's one them:

Within seconds of visiting this site, a quick scan was made of my blog, and out spat a rating. I guess it's alright.

Monday, July 2, 2007

Just some notes on religion and war

I am not a religious person. There may or may not be a God. And if there is, I'm not sure the supernatural law and order that springs from Him can be translated into a certain way of behaving here on earth, for humans. Nevertheless, I think religions need a little defending right now because they're being blamed for much more than they deserve. There are a number of high-profile atheists these days, like Richard Dawkins, that attack religion and claim religious people are morons for believing in such superstition. Evolution is patently correct, they argue, and anyone that doesn't see that is beyond approach. Now, this is bad enough. Religious people are not morons: it's very natural to believe in a higher power (in fact, some evolutionary psychologists now say there may be evolutionary explanations for religious belief). But there is another very important claim.

Some of these atheists believe that if religions were to disappear, so would many of our conflicts and wars. They cite examples like the Crusade, religious fundamentalists-turned-terroists, and others. The explicit justifications for fighting for these groups is often religious. These groups say that God expects certain things from people, and their enemies are not living up to these expectations. Therefore they should be overcome, and possibly destroyed. It seems so clear then that if religion were out of the picture, so would the justification for many of our wars.

But this is to take an overly literal approach to the reasons for fighting. At times religious arguments are employed to mask more worldly reasons for war. War may be undertaken to address poor economic conditions; to consolidate lands; to get back at an aggressor; or to simply conquer another people. And the only way to ensure public support is to argue that God is on your side. But it's only rhetoric. The leaders of violent movements are not necessarily religious when making religious claims. Getting rid of religion will therefore solve nothing.

Of course, there are other cases in which movements are genuinely backed by religious conviction. About those I would admit the uncompromising certainty of religious belief is at fault. And yet, I can't help but believe there would be a balancing out if religion were to disappear - in the form of more conflicts and wars. We would get rid of one reason for war, but find that human beings are increadibly adept at dreaming up new ways to oppress one another. In this respect, I've been influenced by Sigmund Freud's book, Civilization and its Discontents. In it he argues that war and conflict is an unavoidable feature of humanity. We might develop communities of good will and cooperation, but only in relation to an opposing group. A group we conceive of as the Other, in relation to which we define ourselves. So, if war and conflict is unavoidable, perhaps religion is ultimately excused.

Some of these atheists believe that if religions were to disappear, so would many of our conflicts and wars. They cite examples like the Crusade, religious fundamentalists-turned-terroists, and others. The explicit justifications for fighting for these groups is often religious. These groups say that God expects certain things from people, and their enemies are not living up to these expectations. Therefore they should be overcome, and possibly destroyed. It seems so clear then that if religion were out of the picture, so would the justification for many of our wars.

But this is to take an overly literal approach to the reasons for fighting. At times religious arguments are employed to mask more worldly reasons for war. War may be undertaken to address poor economic conditions; to consolidate lands; to get back at an aggressor; or to simply conquer another people. And the only way to ensure public support is to argue that God is on your side. But it's only rhetoric. The leaders of violent movements are not necessarily religious when making religious claims. Getting rid of religion will therefore solve nothing.

Of course, there are other cases in which movements are genuinely backed by religious conviction. About those I would admit the uncompromising certainty of religious belief is at fault. And yet, I can't help but believe there would be a balancing out if religion were to disappear - in the form of more conflicts and wars. We would get rid of one reason for war, but find that human beings are increadibly adept at dreaming up new ways to oppress one another. In this respect, I've been influenced by Sigmund Freud's book, Civilization and its Discontents. In it he argues that war and conflict is an unavoidable feature of humanity. We might develop communities of good will and cooperation, but only in relation to an opposing group. A group we conceive of as the Other, in relation to which we define ourselves. So, if war and conflict is unavoidable, perhaps religion is ultimately excused.

Sunday, July 1, 2007

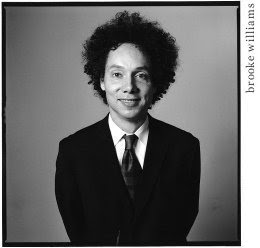

Malcolm Gladwell

I'm a great fan of Malcolm Gladwell's. He's increadibly adept at distilling academic work into simple, and, at times, beautiful prose. But there is a downside. He tends to pare people down into mere statistics. For example, in one blog entry - following the ides of his book, Blink - he says that when you are speaking to a stranger, it is alright to bring up topics that person's race, sex, etc. are commonly associated with. So, when speaking with white-southern-business men, Gladwell regularly brings up college football. The reasoning is that if he acts according to the average interests of a demographic, things will work out for him, and his conversation partner, more often than not. Alright. But what about the effect of this strategy on the individual? It is increadibly disheartening being confronted by someone that sees you as a mere statistical average. Yes, it will work on average. But when it doesn't , the individual is left very wounded. He or she is left feeling like a jelly fish: transparent to all, an unwitting open book. And perhaps that outweighs the benefits. Perhaps that suggests we should not employ such a strategem.

I'm a great fan of Malcolm Gladwell's. He's increadibly adept at distilling academic work into simple, and, at times, beautiful prose. But there is a downside. He tends to pare people down into mere statistics. For example, in one blog entry - following the ides of his book, Blink - he says that when you are speaking to a stranger, it is alright to bring up topics that person's race, sex, etc. are commonly associated with. So, when speaking with white-southern-business men, Gladwell regularly brings up college football. The reasoning is that if he acts according to the average interests of a demographic, things will work out for him, and his conversation partner, more often than not. Alright. But what about the effect of this strategy on the individual? It is increadibly disheartening being confronted by someone that sees you as a mere statistical average. Yes, it will work on average. But when it doesn't , the individual is left very wounded. He or she is left feeling like a jelly fish: transparent to all, an unwitting open book. And perhaps that outweighs the benefits. Perhaps that suggests we should not employ such a strategem.Gladwell approaches the question of racism, and one's degree of racism, in much the same way here. I think he would be a little harder (justifiably) on Michael Richards, if he wasn't so confined by definitions and categories.

Name: Malcolm Gladwell

Age: 43

Ethnicity: Mixed (mother is Jamaican)

Profession: Staff writer for The New Yorker

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)